‘I fully expected a body recovery’: Man rescued after being pinned by 700-pound boulder while hiking near Seward

A couple was hiking along Fourth of July Creek when a rockslide sent boulders tumbling down to the riverbed

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) - This past Saturday, the day began like any other for Kell Morris, 61, who ventured with his wife out on a Seward hiking route that morning.

They had decided they’d do a day hike, choosing to go out along a quieter path – without any designated trail – during the busy holiday weekend, with the intention of turning around once they’d felt they’d gone far enough.

Instead, a giant boulder derailed those plans, tumbling from the canyonside and triggering a multi-agency rescue effort.

The call

On May 24, just before noon, Seward Fire Department crews were alerted to an emergency in the Fourth of July Creek headwaters. A 911 call had come in from the relatively remote location across the bay from downtown Seward.

That in itself seemed like a feat, Seward’s fire chief said, as cell service is undependable at best in that area.

A woman had called in, stating that her husband was underneath rocks and stuck in Fourth of July Creek. That waterway pours into Resurrection Bay but originates from a series of glaciers, icefields, and snowfields in the mountains that border the coast.

“The call came in by cell phone to Seward Police Department dispatch,” Fire Chief Clinton Crites said. “Luckily, they had cell service. And we had GPS coordinates right away.”

With coordinates to reference, crews were now looking for 61-year-old John Morris, who had reportedly been pinned by a boulder miles down the creek. He was stuck there, ice-cold water flowing around him and the water levels rising by the minute.

Knowing a journey was ahead just to get to where Morris was located, SFD immediately enlisted other agencies for an assist.

“We knew we were going to have to drive from here all the way over to [the Seward Marine Industrial Complex], which is a 15- to 20-minute ride, just by vehicle,” Crites said. “We immediately knew we were in for a substantial hike, just looking at the GPS coordinates.”

Crites immediately called for partner aid, he said. Along with Seward fire crews, the Seward Volunteer Ambulance Corps and Bear Creek Volunteer Fire Department established a command post nearly two miles from where Morris was known to be located.

From there, a whole team of people began their trek toward him on foot and all-terrain vehicles; it was a slog, with SFD describing a slow but steady advance toward the man, and characterizing the terrain as “extreme.”

“We all pretty much met at about the same time over at the quarry entrance at SMIC,” Crites said. “And then, from there, it was a two-mile trek up the canyon, up the riverbed, through really large boulders, to get to the patient. The ATVs were not doing well in that environment; it was very extreme.”

About halfway to Morris, the ATVs were no longer viable for the journey, Crites explained. Thankfully, SFD had already made contact with a passing helicopter — that just so happened to have a volunteer fire crew member on board — and that aircraft was simultaneously en route to the accident site to assist.

“He heard the call and asked his pilot, he said, ‘Hey, do you mind if we go to have a look?’” Crites recalled. “And they saw how treacherous it was, and that we were going to need assistance.”

With rocky terrain preventing a proper helicopter landing, that crew got close enough to allow one of the people onboard to jump from the aircraft, making him the first to arrive on scene.

The hiker

Morris, who hails from Texas, is now in Alaska working as a foreman for Catalyst Marine Engineering in Seward. Before that, he rodeoed, served as a Marine, and raced sailboats around the world, he said.

On Saturday morning, he and his wife, Joanna Roop, packed up for a more leisurely day trip, removing some of the winter gear that had been sitting in their usual packs but making sure to include extra snacks, water, and dry clothes for the hike.

“We were planning on eating a little light hiking lunch along the way anyway, since we’d be out most of the day,” Morris said. “Basically, our plan was to follow Fourth of July Creek up to Godwin Creek or river, and then follow it up through the canyon area to the moraine lake, the Godwin Glacier moraine lake. That was the plan.

“We’re slow, we’re there to see the sights, we’re not in a hurry,” he said. “So, we keep an eye on the time, and when we get to a certain time, we turn around and come back whether we made it to our destination or not.”

Given there was no trail the couple was following, the hike wasn’t expected to be easy, but Morris felt comfortable with taking his lighter day pack that day. One of the things left out of his bag before setting off on Saturday, however, was a key item he wished he had.

“It was this beautiful, beautiful day,” Morris said. “We still had, like, stocking caps and stuff like that, extra clothes, extra socks, fleece, regular matches, that kind of stuff.

“But we took the hand warmers out for some reason. Can’t even remember why. But that turned out to be a slight mistake.”

The fall

In reflecting on his experience, Morris said he and his wife were having a great time just being in the wilderness, but the area proved to be “tough going.”

“A lot of rocks that are in the river bed,” he explained, “but we were having a great day. We saw mountain goats, a lot of bear signs, some moose sign, which was promising. We just were having a good day, heading up the river.”

There’s no designated trail where they were adventuring, Morris said, so he and Roop did quite a bit of meandering, crossing the river here and there, wringing out their socks every so often.

Nobody goes up that way, he added, which is one of the reasons a less populated trail was chosen for the day.

“They’re taking the normal trails,” he said of the holiday weekend crowds. “We decided to go up there to just try and get away from the regular tourist crowds.”

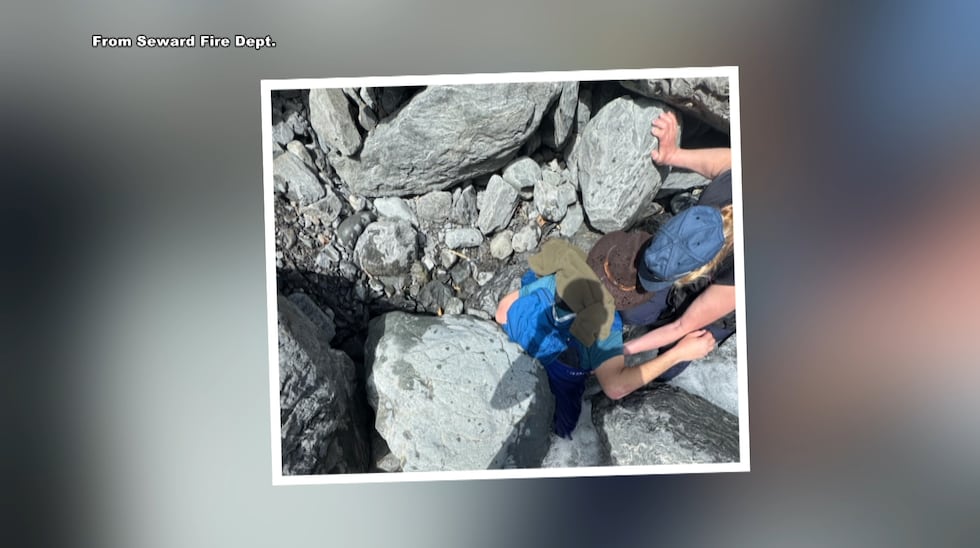

The two were up in the canyon areas near the moraine lake and scouting for a spot to cross the river from the north side. Roop went downriver just slightly, recalling a couple of potential crossing locations; Morris moved up through some rocky terrain, noticing that it was turning into a precarious, 45-degree-angle slope, with boulders that were not especially loose but also not particularly stable.

“There was a pile of boulders sticking out,” Morris said. “I took a look at it; I did not want to walk under them. It just didn’t look good. So I walked as high up against the cliff wall as I could to go around them.”

He was staying 10 to 15 feet away from the rock pile, he said, but couldn’t find a nearby river crossing so started to head back toward Roop.

“I was coming back, and those same group of rocks — crossing in the same place up above them, where I’d crossed before — it all came loose,” he said. “The whole side of that rock scree just came loose, and I was sliding with it.

“Then, it’s a blur,” he said. “I went tumbling. I landed in the water. You could hear the noise that large rocks make as they’re rolling over each other. I landed face-down in the river, and then, I felt the rock hit me in the back and pin me down.”

As it turns out, that rock was a 700-pound boulder that would require the manpower of seven people to move it.

“At that point, it was just, ‘Am I stuck? How big is the rock? Am I okay?’” said Morris, whose shoulders were still above water at this point. “I’m alright. My left side hurts pretty good. I discover that my right side is free, but my left leg, hip, all the way down, is pinned tight.

“Can’t move anything,” he added. “I can feel it, but I can’t move it.”

Roop, a retired Alaska State Trooper who served on the force for decades, had heard the rock slide and was quickly by Morris’ side. Together, they attempted to self-rescue, but the situation was becoming more dire as time went on.

Unable to free Morris after about a half-hour of effort, and concerned about serious injury, Roop had to briefly leave Morris to get a signal to make contact with local dispatchers.

“Don’t go anywhere,” she said.

The rescue

The first outside responder to get to the slide site was Sam Paperman, Morris said. Paperman is a part of the Seward Helicopter Tours team, a longtime member of the Turning Heads Kennel — run out of Seward by Iditarod veterans Sarah Stokey and Travis Beals — and a Bear Creek Volunteer Fire Department responder, according to Crites.

Paperman and his pilot arrived to find Morris and Roop surrounded by rocks, with creek water running underneath them. Morris, who was still stuck under the boulder with ice-cold glacial water surrounding him, was face-down in the water and hypothermic, unable to speak clearly by the time additional rescue crews were on scene, according to SFD.

Roop was even holding Morris’ head out of the water, as the water levels were beginning to rise noticeably around them.

Still, Morris had no idea about the size of the rock that was pinning him down. Paperman and Roop were doing all they could, Morris said, though at one point, the boulder slipped a little bit and started to pinch him a little more.

“I felt really bad, because actually, I think I cussed at young Sam,” Morris laughed. “He was just trying to help!”

Morris would begin to dip in and out of consciousness, but soon, a half-dozen other first responders would arrive to help save his life.

“They actually landed in the riverbed, close to our command post, and picked up three firefighters,” Crites said of the flight-seeing helicopter, adding that those firefighters had to jump out of the helicopter from a few feet up since the aircraft couldn’t land on the rocky terrain.

“Then they came back and picked up three more firefighters and took them up there,” he said. “So we had six on scene within a pretty short while.”

According to Crites, the crews came with key equipment, such as rope and airbags that are typically used for vehicle extrications, but the terrain was making it tough to do anything with the usual gear.

“So it was literally, ‘Okay, guys — one, two, three, and push!’” Crites said. “And they were able — with six of them — to push enough where they could pull him out from underneath the rock.

“It’s pretty unbelievable,” Crites added. “There were rocks underneath him as well. When he fell, smaller rocks fell on top of him, and around his legs and arms. And when the big rock came down, the big rock actually landed on the little bit smaller rocks, and so, that’s how he didn’t get completely crushed.”

Once the rescue crew had gotten Morris free, he was taken out of the water, put in dry clothes, and into warming blankets.

It took about a half-hour for him to come around again, and another hour or so for him to be hoisted out and taken to the Seward Airport before heading to the hospital for a short stay, according to Crites.

“I cannot believe he is as well as he is,” Crites said, explaining that even removing an object from someone who is being crushed can be dangerous, in that blood in the crushed area can become “toxic” when cut off from the rest of the body. Morris was lucky, he said.

“Every star was aligned,” Crites said. “It was a beautiful, sunny day. We had tons of crews available. We had a private helicopter tour company that was willing to help us. We had a cell phone signal.

“You couldn’t have made the stars align any better for this guy,” he said. “I fully expected a body recovery.”

After a two-night hospital stay there to ensure there were no other complications, Morris said he’s feeling pretty good and “ready to go dancing.”

“This isn’t even the worst thing that’s happened to me,” Morris said. “My wife says I’ve used up 20-something cat lives.

“For me, it’s like, ‘Ah, I’ve done it again,’” he said. “But we’ve decided, in our ‘advanced age,’ that we’re going to stick to trails from now on.”

Morris and Crites both expressed gratitude for those involved in the weekend rescue and emphasized the importance of skilled emergency crews, including the people who volunteer with local departments.

“We can’t do this without volunteers,” Crites said. “You don’t have to just fight fire. You know, there’s rescues like we did this weekend, there’s other jobs you can do in other departments.

“We could use hands just washing hose,” he added. “Anything you can do to help your local fire department would be greatly appreciated.”

To learn more about opportunities with the Seward Fire Department, click here.

See a spelling or grammatical error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2025 KTUU. All rights reserved.